I met my wife in late 2006. November 5th, to be exact. We exchanged pleasantries and had a nice conversation over a pizza dinner. Afterwards, it was time to head over to the movies, which was conveniently located on the same block. I have no idea whether or not our decision to attend a raucous screening of the number one comedy in America contributed to our eventual nuptials, but it clearly didn’t hurt. I’d taken dates to the movies before and had...varying results. One time, and mind you, this was in my 20’s, I went on a blind date to a matinee of the animated feature, Robots (2005). Like, what do I do? Make a move during a kid's cartoon since this flick clearly wasn’t made with our demographic in mind? NOT make a move because...come on! It’s a kid’s movie! What will she think? Another less-than romantic evening with a different young lady was spent watching Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), Scott Hicks’ follow-up to his Oscar-winning Shine (1996). A pretty film to be sure, but deadly serious and not particularly romantic. Oddly enough, prior to meeting my wife, my most successful post-movie date ended up being Anaconda (1997). Something about how utterly goofy that movie was must’ve revved our engines. Still, all of those people are dead now, as is the case for all previous relationships once you’re married (that’s how it works, right?), so when my wife and I were practically falling over each other with laughter at our screening of Borat (2006), I knew things were going well. Borat’s comedy is practically relentless. While most American comedies have stretches between the funny bits, many sequences in Borat refused to let up, leaving us breathless. Sydney Pollack’s Tootsie (1982) may not be hysterical every minute, but very few films can boast multiple punchlines in a single scene, all of which land, as well as many outstanding scenes which are often both poignant and hilarious at the same time.

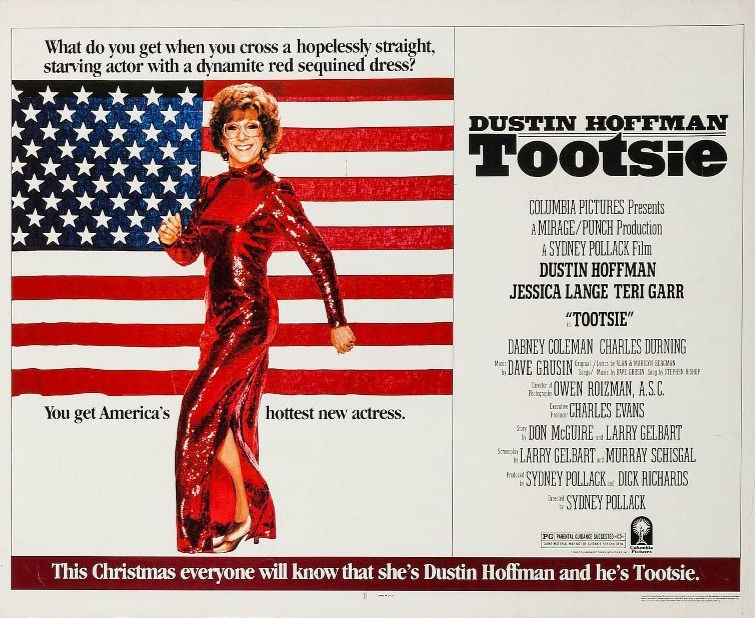

Tootsie has an irresistible concept. A difficult actor disguises himself as a woman to land a role in order to bankroll a play. Honestly, after revisiting the film, I’d completely forgotten about the play angle. I just figured he needed the money and nobody would hire him, so poof! Here comes Dorothy Michaels, who apparently has no social security number nor does she need ID, but never mind about all that. Although quintessentially a New York story, the Tootsie screenplay transcends it’s urban setting by presenting social commentary in an engaging and, most importantly, highly entertaining manner. It’s no wonder the film places high up on Best American Comedy lists.

Larry Gelbart often gets the lion’s share of the credit for Tootsie’s clever construction. After all, his work represents some of the best comedy writing in film, television, and theatre. I try to be sparing with the word ‘legendary’ since it’s been co-opted by a younger generation and applied to twenty-somethings who throw out a sick burn or post a memorable meme. No one could’ve dreamed that the group of writers toiling away on Sid Caesar’s TV programs would reshape the landscape of American comedy. Many of these scribes became iconic and made up a murderer’s row of comedy superstars. I’ve read countless musings by individuals who wish they could’ve been in the same room with Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Neil Simon, Woody Allen, Mel Tolkin, Michael Stewart, and Larry Gelbart. These deans of drollery truly are legends. While Brooks, Reiner, Simon and Allen became highly visible as writer/performers or in Simon’s case, one of the most successful playwrights of all time, Gelbart’s name isn’t bandied about quite as much as theirs, despite being a bit of a tyrant and a blowhard.

This aspect of his personality is on full-display since Alan Alda’s pompous and pretentious Lester in Woody Allen’s amazing Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) is based on Gelbart. Still, anyone who said: “If Adolf Hiter is still alive, I hope he’s out of town with a musical” is all right with me. He certainly would know. Although his first Broadway book credit was the flop The Conquering Hero (detailed in Ken Mandelbaum’s brilliant Not Since Carrie), he’d bounce back in a huge way, co-authoring the book (along with Burt Shevelove, No No Nanette) for the wonderful A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Gelbart is often best remembered for this musical, although it’s important to mention his play Sly Fox, which had a respectable run, and his Tony-winning book for City of Angels, a brilliantly conceived Cy Coleman/David Zippel Hollywood musical satire. Oh, and he was the creator of the M.A.S.H. television series, which happens to be one of the most successful series of all time. He’d be nominated for his second Oscar on Tootsie, having received a nod in 1977 for Oh God!.

In researching Tootsie, it’s clear the script went through several writer’s hands. Though Don McGuire would write a play entitled Would I Lie to You?, the story itself was developed by Gelbart and McGuire (the awesome Bad Day at Black Rock, Artists and Models), while the screenplay credit was shared with Gelbart and playwright Murray Schisgal (Luv). Uncredited contributions would come from Barry Levinson, who ironically would be nominated for his debut feature Diner the same year; Robert Garland, The Electric Horseman and the underrated Deal of the Century (I wouldn’t wear those to a pig’s bris); Robert Kaufman, writer of Richard Rush’s great Freebie and the Bean; and finally, mad genius Elaine May, an incredible script doctor whose own credited work on Primary Colors, The Birdcage, The Heartbreak Kid, Heaven Can Wait, and Nicky and Mikey led her all the way to winning a Tony for Best Actress for The Waverly Gallery. And these are only the “uncredited” writers. Arbitrations at the Writer’s Guild involved so many writers wishing to claim credit that the film’s release ended up being delayed. Of course, there was a great deal of improvisation on the set, notably from Bill Murray. Star Dustin Hoffman also had a great deal of input as many situations and even lines were taken from his real-life experiences auditioning and working in the theatre. Still, someone has to steer the ship, and Tootsie’s impeccable direction comes from the brilliant, yet unassuming Sydney Pollack.

Hoffman and Pollack quarreled furiously during the production, yet you’d never know it based off of their scenes together, where their animosity (which in retrospect turned out to be real) translates into some of the funniest scenes in the film. Pollack was one of those rare filmmakers who also happened to be a fine actor in his own right. It’s well-known that he had no interest in appearing as Hoffman’s agent and was practically forced to do so after the difficult actor (in an example of art imitating life) refused to work unless he got his way. Pollack had begun as a television actor, but giving himself such an important role might’ve smacked of indulgent grandstanding if he weren’t so fantastic in the role. Like Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer, Pollack cut his teeth directing television, beginning in the early 60’s while those two titans had been working slightly longer, since the mid-50's. His first few features are solid, and his uncredited work on the unique The Swimmer (1968) shouldn’t be discounted, but I believe he hit his stride with the brutally dark They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), for which he received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Director.

He was most prolific during the 1970’s, directing six features, half of which in collaboration with Robert Redford: Jeremiah Johnson, The Way We Were, and Three Days of the Condor, one of the few paranoid thrillers not directed by Alan J. Pakula. The Yakuza was, of course, most famous for the high-priced sale of its script by the brothers Schrader, Paul and Leonard, while the Al Pacino-starring racing picture Bobby Deerfield (1977) was an outright disaster. He’d bounce back with the profitable The Electric Horseman (still one of my favorite VHS covers), then continued his hot streak with Tootsie. His epic Out of Africa (1985), for which he’d receive two Oscars for producing and directing, turned out be his career pinnacle. He seemed to slow down after this run, waiting five years to reunite with Redford for the so-so Havana (1990). Perhaps Out of Africa’s large-scale production took a lot out of him, because save for box office hit The Firm (1993), an exciting throwback to his own paranoid thriller work on Condor, his output during the 90’s and early 2000’s was mostly undistinguished and rather dull. For someone who preferred to focus on directing and producing, he ended up giving some very good performances, mainly in Stanley Kubrick’s final feature Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and Woody Allen’s angry Husbands and Wives (1992). His work as a producer during the last 20 years of his life was classy, with The Talented Mr. Ripley, Cold Mountain, Michael Clayton, and The Reader to his credit. His direction on Tootsie feels almost miraculous. Granted, it helps to have a strong story and such willing performers, but complex sequences like the shooting of a scene for Southwest General, the ridiculous soap opera Hoffman’s Dorothy character gets cast on, are done with economy and clarity despite featuring multiple characters at once.

“You can’t argue with results!” I say you can, but considering how artistically successful Tootsie became, not to mention financially, Dustin Hoffman did appear to be on to something. It’s a tricky situation regarding whether to praise a performer for putting their heart and soul into a project but driving everyone around them absolutely crazy. Hoffman’s level of commitment to the craft of acting is virtually Herculean and while most non-showbiz types would regard the work of doctors, nurses, lawyers, etc., as “serious business” and acting as “playtime,” the future Captain Hook would impolitely beg to differ. I won’t ignore the sexual misconduct allegations levelled at Hoffman over the years, but as those investigations are ongoing, if not somewhat forgotten, I’ll focus on his work rather than his off-camera behavior. It’s heartbreaking to discover that someone you admire could turn out to be a son of a bitch. I once engaged in some light arguing on an IMDB forum (before they removed the message boards completely), and although I don’t even think of Dustin Hoffman as my favorite actor, I chimed in on a DeNiro vs. Pacino argument to claim that Hoffman was more versatile than either of them. That’s controversial, but I don’t think anyone can deny that DeNiro/Pacino couldn’t’ve played some of Hoffman’s roles, and vice versa.

I often forget how early Dustin Hoffman hit it big. Sure, he was barely 30 when he was cast as Benjamin in Mike Nichols’ seminal The Graduate (1967), but once you become famous, you essentially stay famous. There are myriad results, with some stars fading away or making severely poor career decisions, but for Hoffman, his commitment to playing difficult roles continuously made him an engaging performer to watch. Midnight Cowboy, Little Big Man, and especially Straw Dogs showed his willingness to play unlikable, or in the case of Dogs, weak individuals, revealing a certain lack of vanity on his part. For me, his run in the mid-70's is astonishing, starting with Papillon, Lenny, All the President’s Men, Marathon Man, Straight Time, and ending with Kramer vs. Kramer, while Agatha represented a slight bump in the trajectory. He was always controversial and often rubbed people the wrong way, with his criticism of the Academy Awards ruffling many feathers, although I found both of his acceptance speeches, the first for Kramer and the second for Rain Man (1988), to be very genuine and articulate. He was able to bounce back quickly from the Ishtar (1987) debacle and I do find some of his work in the 90’s to be fun, although he was beginning to show signs of his sudden penchant for over-acting and scenery chewing. It’s odd to think about the key differences between the progression of Hoffman, Pacino, and DeNiro’s career since they came up around the same time, with Hoffman tasting success a few years earlier.

While DeNiro continued to remain subtle and tended to embarrass himself when he attempted big comedy (The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle), the latter two went big. Pacino became a parody of himself (only redeeming his reputation by taking risky work in HBO dramas and doing theatre work) while Hoffman tried his hand at a variety of studio productions including Outbreak (1995) and Mad City (1997). His last great piece of acting was his Oscar-nominated turn as the Robert Evans-inspired Stanley Motss in the satirical Wag the Dog (1997). After that, it’s mainly been a series of disappointments. He hasn’t stopped working, that’s for sure, but in films like the excellent Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), his acting (obviously they used his star power to get more financing) is particularly terrible and drags down an otherwise great film. He tried his hand at directing for Quartet (2012), with “meh” results. With Tootsie, one can see why he was such an exciting actor even as he neared middle age. Every facet of his neurotic and passionate personality is on display. It’s no wonder that although he was nominated but didn’t win an Oscar, the musical adaptation unsurprisingly awarded its star, Santino Fantano, with a Tony Award.

The supporting cast is flawless. The biggest surprise for many viewers at the time was Jessica Lange, who made an inauspicious debut as Dwan (You know! It’s like ‘Dawn,’ but I switched the two letters to make it more memorable.) in King Kong (1976). Who would’ve thought the pretty but vapid lady from Dino DeLaurentiis’ bombastic giant ape movie would eventually become one of our finest actresses? Her Oscar-winning performance as put-upon soap actress Julie is lovely to behold. It didn’t hurt that she was also nominated in the lead actress category that year for her harrowing portrayal of Frances Farmer, so her ability to play opposite ends of the spectrum was on full display. I believe she deserved her Oscar, but it’s unfortunate that this in turn caused the spectacular Teri Garr to lose out, despite at least being nominated in the best supporting actress category as well. Garr has, in my opinion, a much trickier role, playing a mediocre actress. Constantly being screwed over and led on, Garr gains both sympathy and laughs, particularly when she criticizes Dorothy in front of Hoffman and snatches up the script for the play she’ll be appearing in with him, insisting she’s “a professional” despite Hoffman’s constant deception.

And who wrote said play for which Hoffman’s Michael Dorsey is willing to don women’s clothes to get financed? Jeff, played by the flat-out fantastic Bill Murray. The Illinois-native is a comedic and cultural icon and he had already become a star thanks to Meatballs, Stripes, and Caddyshack. Intriguingly, all of these films, despite his lead role status, were mostly ensemble pieces, while his solo Hunter S. Thompson effort Where the Buffalo Roam (1980) failed at the box office and with the critics. Bruce Vilanch once spoke of his former colleague, the late Paul Lynde; boiling his limited appeal down to that of a great ingredient to be used sparingly. You wouldn’t eat an entire meal consisting of one spice, so he couldn’t be the only component. Bill Murray is a much more accomplished performer by leaps and bounds, but a little of him does go a long way, despite his brilliance in starring roles like Ghostbusters (1984), Groundhog Day (1993) and Lost in Translation (2003). Considering the wildly successful career still ahead of him, it seems almost superfluous to cite Murray as one of the funniest performers in the film, but it’s undeniable. He acts as the audience surrogate, which may be why he’s so hilarious in the role. He says the things we’re all thinking. For instance, he’s constantly pointing out how weird things are getting as Hoffman sinks deeper into the personality and idiosyncrasies of Dorothy Michaels. His pretentious but adorably sincere monologue about only wanting to open a theatre during a rainstorm is a beautiful illustration of an artist’s desire to make a grandiose statement about life. And of course, he brings the house down when he catches Dorothy/Michael in a compromising position and simply states: “You slut.”

The film crew on Southwest General is peppered with awesome character actors who bring just the right level of deadpan humor and authenticity while making this trashy little soap. Chief among them is the Southwest Gen. director, Ron, played by expert scumbag actor Dabney Coleman. Pollack initially had cast Coleman in the role of Hoffman’s agent before he was forced to play the part himself, but the role of a philandering, sexist, asshole director fits Coleman like a glove. When Dorothy insists that he call “her” by her name, he looks to the heavens and says “Oh, Christ,” as if internally saying, “This ridiculous women’s lib crap is killing me.” He’d played this type of role before, so hopefully he wasn’t too bummed that he was essentially doing a retread of his famous performance as Franklin Hart Jr. in 9 to 5 (1980). I think he’d begun laying the groundwork for this kind of character in his brief but memorably snobby turn in Ted Kotcheff’s North Dallas Forty (1979). Never likely to show up anywhere without wearing a suit, he’s often cast as some sort of authority figure and is always solid, even when the material isn’t quite up to par. For a hot minute there, they kept trying to make him an action star with Cloak & Dagger (1984) and Short Time (1990), both movies being relatively good but box office disappointments. He fares better in supporting roles, like in WarGames, Hot to Trot (he’s a real horse’s ass in that one), Meet the Applegates, Clifford, The Beverly Hillbillies, and the extremely unpleasant Commodore on Boardwalk Empire, a part which sadly would’ve been a lot larger had it not been for his throat cancer diagnosis, which caused his role to be greatly reduced and mostly mute.

The no-nonsense producer Rita (Doris Belack, who had soap experience of her own from One Life to Live) takes a liking to Dorothy’s take-no-prisoners approach to acting. The future ‘Chief’ who was constantly searching for Carmen Sandiego, Lynne Thigpen, appears as Jo, the script supervisor. She’d already leant her mellifluous voice and mouth-only to The Warriors (1979), and she’d go on to a have a strong career in films like Lean on Me, Just Cause, The Player, and Blankman. Future Oscar-winner Geena Davis shows up in a small role as one of the fictional nursing staff. The real scene-stealer is Punky Brewster and Police Academy actor George Gaynes as John Van Horn, the buffoonish, long-time doctor at that “nutty hospital.” Unable to remember the simplest of lines without a teleprompter; his deep, sonorous voice make all of his idiotic musings and actions all the more hysterical. The moment in which he plants a big smackeroo on Dorothy and strides away is a particular delight. His physicality fortunately makes a potential rape scene, preceded by his singing of Guys and Dolls’ “I’ll Know,” funny rather than uncomfortable. In many ways, Gaynes’ character is something of a prototype for the role Jeffrey Tambor would play as Hank Kingsley on The Larry Sanders Show years later. What sets Tootsie apart from many other comedies is its inherently human qualities.

Midway through the film, Dorothy is invited to spend the holidays with Julie and her father, Les. The first time I watched Tootsie I found this sequence quite dull since the wackiness took a backseat to sentimentality. This was a completely incorrect conclusion to draw. The scenes at the farm, though a bit schmaltzy thanks to the catchy but mushy Oscar-nominated Grusin-Bergman collaboration “It Might Be You,” are quietly moving. Although a scene between Lange and Hoffman in bed together is heartwarming, the main reason the film doesn’t dip in quality or interest is thanks to the work of one of the finest character actors who ever lived, Charles Durning. As Les, he’s a man of few words but of genuine good cheer. A real gentleman, he communicates his growing affection for Dorothy through a look or two. His ultimately futile infatuation actually comes off more tragic than comic due to Durning’s absolute commitment to how enchanted he appears to be by Dorothy. Later, when he proposes marriage to an increasingly frazzled Hoffman, he even gets to show off his dance moves, an aspect of Durning’s talent that often came in handy for films like his Oscar-nominated turn in The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982) and O Brother, Where Are Thou? (2000).

The proposal comes along during one of the film’s finest moments. A jaw-dropping series of scenes in which Michael has the night from hell. First, he tries to kiss Julie as Dorothy, forgetting himself, or rather, herself. In a moment which at first seems somewhat homophobic but actually turns out to be Julie’s realization that Les is pining for an unattainable woman. The proposal comes next, followed by Van Horn serenading Dorothy until coming up for a drink. He proclaims his uncontrollable passion for Dorothy and Michael is only saved by the arrival of Jeff, who is reassured by Van Horn that “nothing happened.” It gets worse as Sandy shows up and Michael only tells a half-truth, claiming he loves another woman but not revealing his alter-ego. He worries Sandy’s reaction to losing a part she was up for to a man dressed as a woman would send her over the edge. It’s absolute pandemonium and a text book example of things coming to a head.

The technical side of the film deserves special note as the film is immaculately shot and edited. Compared to other cinematographers, Owen Roizman has a relatively small number of credits to his name, but what a line-up! They include genuine classics like The French Connection, The Exorcist, The Taking of Pelham One-Two-Three (whose seemingly simple look was apparently quite difficult to pull off according to an interview Roizman gave), Network, and was Pollack and Lawrence Kasdan’s regular DP for years. He was surprisingly nominated for an Oscar here, considering how un-showy the photography is, but I’m always encouraged when that happens since it’s much more difficult to light an interior naturally rather than shoot in outdoors. The editing by father-son team Frederic and William Steinkamp (who between them edited nearly all of Pollack’s films as well as Adventures in Babysitting and Scrooged) is spot on, if a little on a sitcom level, with the famous exchange: “No one will hire you.” “Oh yeah?” immediately followed by the reveal of Hoffman as Dorothy accompanied by Dave Grusin’s infectious score. A less-famous but quite obvious cut arrives when Dorothy babysits for Julie and is assured her daughter won’t wake up. A quick cut reveals a nightmare scenario where the child is screaming and inconsolable.

There are so many memorable scenes: the opening credits with Hoffman’s various audition disasters; Garr being coached and unable to get angry; all of the scenes between Pollack and Hoffman, particularly their first encounter and later Pollack’s confusion while Hoffman explains the sexual dynamics of Dorothy and Michael’s various relationships; Les extolling his feelings on men and women and this “equal business,” but nothing compares to the climactic live taping of Dorothy’s party scene for Southwest General.

Due to her popularity, Dorothy is signed on for another year, so Hoffman is desperate to get out of this increasingly tenuous situation. Earlier I described the idea of relentless comedy; a scene in which the laughs come fast and furious, and this finale is a shining example of an unyielding approach. As Dorothy is about to say her scripted dialogue, she stares at Julie. Michael decides to get himself off the show once-and-for-all. He improvises an increasingly insane monologue, which is made even funnier when his stammering of the word “and” is followed by a cutaway to Van Horn, who is nodding on each “and,” and was probably the inspiration for the “spike through my head” bit on The Kids in the Hall. I hadn’t watched Tootsie in many years, but I still occasionally watch this particular scene on YouTube just because it’s so hysterical. The atomic explosion of comedy which comes when Michael rips off his wig, revealing himself to be a man is phenomenal. Sandy screams, the contents of Les’ sandwich fall out, a crew member faints, Rita is shocked but somewhat amused: “I’ll be damned,” Ron, egotist that he is, thinks this is the reason Dorothy never liked him, and James asks whether Jeff knows about all this. Julie walks up to Michael and socks him in the gut.

The film has a brief epilogue that fortunately doesn’t throw a title card up stating “Three Months Later,” and Michael reconciles with a distraught but philosophical Les. In a clever touch, Michael and Julie’s future is left somewhat ambiguous as they discuss Dorothy’s wardrobe and walk away from the camera.

Somehow, the subject of male chauvinism, women’s rights, the dynamic between men and women, finding one’s self, and the struggles of an artist are presented in an earnest and refreshing fashion. Although there’s plenty of aggression in the film, there’s also a gentility, perhaps best defined by Dorothy’s ballsy attitude coupled with her southern accent. Why is Tootsie one of the best comedies ever made? Because it says so much without anyone even noticing it’s saying anything at all until the credits roll.

Comments