With over a century of material available today, up-and-coming filmmakers are being challenged to (heaven forbid) be more creative when attempting to break new ground. It’s easy to check out a film that tried something new and fresh because so much has come before. Did Sergei Eisenstein say to himself, in his imitable Latvian/Russian: “These editing techniques will be studied and imitated for years to come!” Did Robert Altman think, “Overlapping dialogue will be my calling card.” Did Errol Morris believe that he could exonerate an innocent man through the power of film? Or was he just following his muse and thought an incarcerated man’s story would be interesting? Hindsight is 20/20 and before his untimely death, writer/director Bob Clark would imply that he was looking to break new ground on what would be his third feature, the holiday horror classic Black Christmas (1974). Far be it for me to question a filmmaker who made some legitimately great movies, but I think it’s more likely he looked at Roy Moore’s original screenplay, first titled “The Babysitter” and later “Stop Me,” and decided to do what came natural rather than the tried-and-true formula of most genre efforts up to that point. Equal parts ferocious, creepy, and hilarious, Black Christmas beautifully shows what can happen when a director with total artistic freedom uses a simple platform to manipulate and subvert a genre that hadn’t even entered its golden age yet. While the slasher genre wasn’t born in the chilly streets of Canada, this pioneering effort nevertheless laid the groundwork and remains influential even today.

“The easiest way to get a movie financed is to do horror or porn...and I wasn’t going to do porn.” So said Bob Clark, the future director of Rhinestone and Baby Geniuses, so take that for what it is. By the early 70’s, the Louisiana-born director had made Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) and Deathdream (1974) in Florida, but his first taste of working with a real budget and real movie stars came during the post-production of Deathdream. The editing happened to take place in the Great White North, aka Canada, and Moore’s script came to his attention. Sick and tired of the “inaccurate portrayals of American college students as idiots,” which he compared to Beach Blanket Bingo, he found Moore’s spin on the old babysitter urban legend intriguing, but in need of a major overhaul. Inspired by the heavily diluted story of Janett Christman, who’d been murdered on March 18, 1950 while babysitting, Moore’s story was essentially the prototype for Fred Walton’s 1979 hit When a Stranger Calls, but Clark was interested in giving his female characters intelligence and wit. Despite his horror roots, Bob Clark isn’t a particularly macabre filmmaker. In fact, he had his name removed from the 1974 production of Deranged due to its graphic nature. Re-writing about half the script, his decision to set “Stop Me” in a sorority house and remove the urban legend’s murder of the children was astute, very much the way he regarded his female protagonists. With these changes, he’d direct a film that set the tone for Canadian horror.

The story of a mad slasher stalking college teens is nothing new, particularly if you grew up on a steady diet of 80’s slasher flicks made in the wake of Halloween and Friday the 13th, but in 1973, this was still a very novel and unthinkable concept. Vision Four, along with the CFDC (Canadian Film Development Corporation), provided what would amount to a $671,000 budget which Clark and on-set producer Gerry Arbeid would squeeze every penny out of. “Minimize waste” was Clark’s motto. Of course, despite heavily Canadian elements like hockey (courtesy of Art Hindle, 5 years away from The Brood), certain alcoholic beverages (Labatt’s 50 Ale), the University of Toronto, and more than a few “aboots,” the film attempts to convince the audience that we’re in the good ol’ U.S. of A with a generous smattering of American flags. Still, despite Canadian horror basically being a non-entity since David Cronenberg was still a couple years away from directing Shivers (aka It Came From Within), the production managed to attract a name-star, and the rest of the cast in turn followed.

I suppose we have the spirit world to thank for getting Black Christmas made. As I recall, when my high school English class saw Franco Zeffirelli’s highly successful adaptation of Romeo and Juliet (1968, starring Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey), no one freaked out when we saw them hop out of bed in the buff. Still, I’ve heard stories about some teachers lamely attempting to cover the screen during this particular scene. Remember, this would’ve been a VHS tape, so no quick skipping ahead was available. This gorgeous adaptation made the then-fifteen-year-old Hussey world famous. Looking to get past the disaster that was 1973’s bloated Lost Horizon, she visited a psychic, as she was wont to do, and was informed she would make a film in Canada and it would be very successful. So, all you apparitions, goblins, poltergeists, and all-around perverted ghosts who just want to watch us all get naked, we horror fans salute you.

Hussey plays Jess, our final girl, but in a twist that wasn’t even a twist since the tired trope of the final girl’s presumed virginity wouldn’t be exploited until years later, she’s not only pregnant, but she’s determined to have an abortion. Her aspiring concert pianist baby daddy Peter, who must’ve just got back from space since he’s played by Keir Dullea (2001: A Space Odyssey), insists that she will not be terminating the pregnancy. He even goes so far as to call her “a selfish bitch.” Hussey’s presence prompted Dullea to join the production since her fame indicated that the film would indeed be “a real movie.” The timing of Jess’ announcement isn’t particularly convenient since Peter’s been up for three days straight, practicing for his big audition in front of university big wigs. I can’t say for sure, but he’s either distraught because of his exhaustion and desire to marry Jess, or he’s just jealous that he’s only got a puke-green turtleneck while Jess has the most epically ridiculous sweater ever seen by human eyes.

Rounding out the cast is the actual good girl, Clare Harrison (Lynne Griffin - Curtains, Strange Brew), who excuses herself after a particularly disturbing episode with the sorority’s obscene phone caller. The mousy Phyl, played by the Emmy and Tony-winning SCTV alum and comedy legend Andrea Martin, is equally disturbed, but appears to be made of slightly sturdier stuff. She’d end up replacing fellow Canadian comedy legend Gilda Radner after Radner had to bow out to become part of a little sketch show called Saturday Night.

Best of all though, is future Lois Lane herself, Margot Kidder, playing the resident alpha and boozehound Barb. She smokes, drinks “I’ve had a couple,” and doesn’t take any shit from anyone, including the prank caller and her jet-setting mother, whom she calls “a gold-plated whore.” No wonder she claims her nickname is “The Tongue.” Kidder had yet to become a megastar in Superman, but she’d appeared in Brian DePalma’s psychological thriller Sisters (1973), so her star was on the rise. Oh, and she was definitely method acting, at least as far as the boozing goes. Clark describes her as wonderful and “crazy as a bed bug.” She’d often be driven to the set along with Olivia Hussey and would usually be hung over, groggily attempting to make the more strait-laced Hussey laugh. Clark encouraged her ballsy, hysterically profane performance, prompting her to challenge herself with the question: “How far can I push this?”

Kidder’s work here is frankly stunning and her star quality is obvious. It could be easy to boil her character down to a hard-partying wild child (who enjoys seeing little kids get “schnockered”), who has a way with words, “Why don’t you go find a wall socket and stick your tongue in it? That’ll give you a charge!” or as a well-informed individual who can impart helpful facts to uncomfortable guests, like a long story about how some species of turtle can screw for three days straight. However, her own depression and pain are obvious in her drunken rants and sadness over being left behind during Christmas break. Like seeing John Candy in another Canadian production, the masterful The Silent Partner (1978), it’s a bit odd to see future comedy stars play straight roles, and it’s a testament to Andrea Martin’s chameleon-like talent that if she’d been called upon to play Barb, she could’ve done it quite easily.

The movie studios of old insisted that the villain of any film be punished by the time the credits rolled. After that dated, ridiculous mandate became old hat, filmmakers were able to indulge in their darker instincts, and the still-impressive and fresh depiction of the enigmatic, deeply disturbed killer Billy remains unapologetically creepy. The most groundbreaking and refreshing element of Black Christmas is the decision to leave the identity of Billy a mystery. All we get are brief glimpses of shadows, silhouettes, obscured views, hands, and most terrifying of all, an iconic closeup of the killer’s eye through the slit in a door. The iris and pupil appear to be on fire; a hellish red flame reflecting upon it, and while this effect was apparently achieved using a special contact lens, there are appropriately conflicting and therefore haunting stories about whose eye is in that shot. Camera operator Bert Dunk believes the eye belongs to Keir Dullea, but Dullea doesn’t recall shooting this particular moment, while Clark simply can’t remember whose eye it was at all.

The red herring of the film is Peter, whose anger over Jess’ abortion plan and his botched audition fuel the police’s suspicion of him. If the film weren’t so engrossing, observant viewers could rule out Peter’s guilt rather quickly considering his presence following a tense closeup of Jess receiving another phone call from Billy and his multiple personalities battling themselves. Instead, the possibility of Peter being the killer appears genuinely possible after he happens to stop by the house directly after Billy very nearly murders Jess. Considering how upset he’d been in the previous scenes, his relatively gentle demeanor is off-putting, to say the least, so Jess feels the need to defend herself in the most brutal fashion possible. This response feels appropriate since an offscreen Billy had literally grabbed Jess’ hair and yanked it with all his might.

The women of Black Christmas are strong and very capable, while most of the men are ineffective scolds; emotionally impotent and inept. This may be the reason why some of the sorority sisters, particularly Barb, shrug off the obscene calls as being the work of a pervert and a “fucking creep.” Men aren’t powerful or influential in this particular universe, so hearing a “moaner” on the phone is just another way pathetic men are trying to get a rise out of intelligent young women. Particularly amusing is Hussey’s pronunciation of the word “moaner.” The Argentinian-born but English-raised Hussey calls out “It’s the moaner,” but her accent makes it sound as though she said “Mona.” Who the hell is Mona?!

The dialogue in the opening prank call is lurid, salacious, and shocking. Even today, it’s astonishingly foul, with graphic sexual innuendo and the c-word bandied about with abandon. The scene is beautifully staged as the camera pans to each of the women’s faces, registering their disgust and fascination. Clark himself was asked more than once by younger viewers whether he’d added those curse words in for later releases since they couldn’t believe that sort of language would’ve been tolerated at the time. Looking at the film now, he’s expressed both surprise and amusement at the level of vulgarity that he, acting as one of Billy’s voices, along with actors Nick Mancuso (Death Ship, Under Siege) who performed his Billy voice while standing on his head to achieve a gutteral effect) and Ann Sweeny (The Incredible Melting Man) threw into the mix.

Billy’s rants about “Agnes” and his pleadings to “stop it” are baffling, but if one listens carefully, there’s a twisted logic to his ravings. Clark later explained that Billy is a young boy who likely murdered his abusive parents, but he in turn abused his sister, Agnes. He locked her up, probably for several years, but she escaped, so his personality has split between Billy, who hates girls that run away and don’t do what he says, and Agnes, who hates boys for the abuse they’ve wreaked upon her. In essence, no one will be spared their wrath, not even a 13-year-old girl who unluckily crossed paths with Billy during a walk through the park. Although the girl’s body is never shown, members of the search party, led by Police Lieutenant Fuller (John Saxon) on a cold, wintery Canadian night, discover the remains of the girl’s body and the devastation on her mother’s face is all we need to know.

John Saxon has made a career out of playing men of action or authority figures. Through Enter the Dragon, Tenebrae, Battle Beyond the Stars, Mitchell, Blood Beach, and A Nightmare on Elm Street, he’s the ultimate cult actor. Yet his presence in the film very nearly didn’t come to pass. Clark and producer Arbeid had originally cast the great Academy Award winning character actor Edmond O’Brien in the role of Lt. Fuller. O’Brien was getting on in years, but his work in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and White Heat were still fresh in filmgoers (and the producer’s) minds, so although he came off of the plane in a wheelchair, they felt he’d add a level of class and professionalism to the production.

Unfortunately, after Arbeid and Clark found that not only was O’Brien unable to do basic tasks like put on a shirt, but he was also suffering from early on-set Alzheimer’s. During dinner at a restaurant, he claimed he was going up to his room. Clark and Arbeid replied that they weren’t at the hotel, which only served to confuse the veteran actor. O’Brien had arrived a few days prior to the shoot and the team considered whether it might be possible to struggle their way through, but the very first shot for Lt. Fuller would be during the search scene on a bitterly frosty evening, so the difficult decision was made to let O’Brien go, despite his insistence that he could perform the role, which might have been possible if they’d been able to get him when he was lucid.

Saxon had received the script much earlier and expressed interest, but was informed that the pages had been sent in error, which may be true, but it’s far more likely that the production simply wanted a bigger name for the part. Stories diverge here as the film’s composer Carl Zittrer claims that he was acquainted with Saxon and placed a frantic call to him personally. Saxon, who may or may not be misremembering, merely stated that he received an urgent call, presumably from his agent, about whether he could get on a plane today and get to Toronto for a shoot that evening. Regardless of who called him, he got to Toronto, went straight to wardrobe, and two hours later, was standing in the 10-degree chill, delivering dialogue he’d just learned. An absolute pro, all the way.

The death scenes in the film are expertly staged and quite frightening. The use of a subjective camera wasn’t completely new; Michael Powell had used a version of it in Peeping Tom (1960) which was a literal camera with a blade in the tripod leg, and even farther back, Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932) used a tracking shot to portray Jekyll’s point-of-view. Black Christmas’ director of photography Reginald H. Morris was Bob Clark’s regular cinematographer for over 15 years (Murder by Decree, Loose Cannons), but his talents would also be utilized during the 70’s for the great Man vs. Nature movement, for which he shot The Food of the Gods and Empire of the Ants. His work is evocative, with some great split focus diopter work, and very sinister, but this is one of those times when the contributions of the camera operator can’t be ignored.

Billy’s subjective camera point-of-view, shot with an extremely wide lens that skews the perspective and essentially makes the audience complicit in Billy’s crimes, was achieved through a rig built by Bert Dunk that kept the camera off-kilter and somewhere between handheld and smooth. The Steadicam was still being developed by Garrett Brown, and this version had the same basic concept; giving Dunk the ability to not only climb along the outside of the sorority house, but reach his hands into the frame and smash various items as he portrayed Billy freaking out while hiding in the attic. Coupled with Billy’s savage yelling and shrieking, it makes for a nerve-shattering experience. Using a subjective camera is also a subtle way to keep the audience on edge, since one begins to question whether any particular shot is merely the camera...or the killer.

The first kill is ingeniously staged, with Billy hiding behind a plastic dryer cover, which in turn is covering the camera and makes for a blurred image. His victim even knows someone’s back there, but while she’s weirded out, she also assumes it’s one of her sorority sisters trying to pull a prank. Her corpse ends up wrapped in plastic, sitting in a wheelchair in the attic for the duration of the film; the house cat Claude hopping up on her lap to lick at the plastic (which in reality was covered in cat nip). The murder of the house mother is also nifty, though a bit outlandish, but it’s saved by a well-built scene of delayed suspense. The finest kill comes with the attack on Barb. Beautiful crystal figurines are laid out around her bed and Billy helps himself to a particularly long-horned unicorn. He stands over her, with only a single eye showing in the light, and he reassures the sleeping Barb that “it’s okay...it’s me, Billy.” Her death, cut together by another longtime Clark collaborator, editor Stan Cole, is juxtaposed brilliantly with the singing of adorable moppets serenading Jess with carols. In a fascinating and fortunate accident, a shot in which Barb’s bloody hand flails about appears to be jittering. It perfectly adds to the horror of the sequence but it was actually due to the film’s magazine being improperly loaded and causing the shake.

John Carpenter was a fan of Black Christmas and even collaborated with Clark on an idea about babysitters and a masked killer. When asked what a hypothetical sequel to Black Christmas would look like, Clark replied to the future director of The Fog and The Thing that Billy would’ve been caught and put in an asylum, but almost a year later would escape and return to the sorority house to kill again. Keeping with the holiday theme, this sequel would be called Halloween. Clark has always been very gracious and humble about his contribution to what would eventually become one of the most important slasher films ever made, and has made clear his adoration for the work and Carpenter (and Debra Hill)’s authorship of the subsequent film.

Although the darkness of the film, helped in no small part by the uniquely warped music by Carl Zittrer, who’d work with Clark for nearly ten more years, is indeed harrowing, I’d be doing the film a disservice if I didn’t also make it clear that the film is also flat-out hilarious, with laugh-out-loud moments scattered throughout. Let’s not forget, this is from the director of A Christmas Story (a delicious irony not lost amongst cinephiles) and Porky’s, so he does know how to get a laugh or three. There’s a boatload of humor in the first half of the picture, including a disgruntled student playing Santa “Ho ho, fuck,” a random but very funny poster of an elderly granny flipping the bird, and the constant belittling of doofus desk Sergeant Nash, played by the breakout star of Goin’ Down the Road (1970), Doug McGrath. A frequent Clint Eastwood collaborator (Pale Rider, The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet), McGrath would be cast in Bob Clark’s breakthrough hit Porky’s years later, another film featuring an extended scene of uncontrollable laughter. In Porky’s, the laughter is in regard to the ways in which an unidentified male’s penis could be located, while in Black Christmas, the moronic Nash is fooled by an annoyed Barb that the number for the sorority house is FELLATIO 20880. Saxon and his partner’s laughter can barely be controlled as the befuddled Nash finally comes to the conclusion that “It’s somethin’ dirty, isn’t it?”

While Kidder is certainly the MVP of the film, a close second comes in the form of house mother Mrs. Mac, played by writer and occasional actress Marian Waldman. If you think Barb has a drinking problem, wait until you meet Mrs. Mac. Clark based the character on his Aunt Mabel who, like Mrs. Mac, hid booze bottles all over the house. It’s rather campy and ridiculous, but Waldman has such an outsized personality that it works within the confines of the film. There’s liquor in her toilet, in the hollowed-out confines of a book, and just about any other place you can imagine. She even uses the hard stuff to brush her teeth with. Thank goodness the original choice, screen legend Bette Davis, passed on the role. Although Davis was still a vital actress, I simply can’t see her bringing the kind of train wreck hilarity Waldman brings to the part. 1974 would be a big onscreen year for Waldman since she’d also appear in Deranged: Confessions of a Necrophile for a couple of scenes. In that film, her wildly over-the-top performance just barely manages to escape ridicule thanks to her utter commitment to the insanity of the character. Deranged is a strange beast, attempting to mix humor with graphic violence, so her work is all the more outlandish considering the subject matter. In Black Christmas, her character feels much more realistic and grounded, without sacrificing the brassy theatricality of it. Always drunk, she rails against the cat “Claude, you little prick!” blaming him for everything, and isn’t particularly grateful for the awful nightgown her girls got her, “I’ve got as much use for this as I do a chastity belt” and “I wouldn’t wear this to have my liver out.”

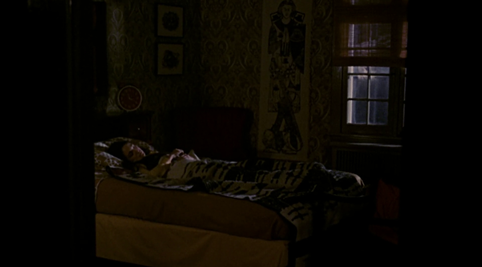

Bob Clark arrived on set armed with copious notes and storyboards, having total confidence in his ability to tell the story he wanted to tell. Knowing how important a horror movie’s setting is, he scoured Toronto for the perfect house to stand-in for the sorority, wanting to find a structure that could match iconic hell houses like the Myers, Bates, and Amityville houses. The quiet and simple cold opening establishes the dwelling and its subtly sinister quality, which is no small feat considering it’s just a house. Clark’s enthusiasm and self-assurance was infectious and made it easier for him to rope several members of the crew, including the producer, production designer and prop master into minor roles. He was also inspired to take more than a few risks, particularly in a complex dolly near the end of the film. The police believe their job is done and a recovering Jess is lying in bed, out like a light. After all of the men leave, the shot continues, holding on Jess for a very long time, until finally dollying past the rest of the rooms, where the brutal murders took place. The delightfully evil twist arrives when we not only discover that Billy is still in the house, but the cops didn’t even bother to look in the attic, so two of his victims are still up there. It’s a bit outlandish, but we’re forced to assume that they believed they’d gotten their man, so why bother searching the house?

Black Christmas is a bold and excellent slice of horror goodness, with great production value and fine acting, with the exception of one individual. It’s bitterly ironic that Olivia Hussey, whose star power drew in other professional performers and likely helped the film break out, is the weakest link of the cast. This is partially due to the script, which asks her to deliver dialogue that doesn’t sound quite right with a British accent. To be clear, she isn’t terrible in the film; the quieter moments with Peter are fine, but the main issue is anything involving the killer. She seems to be under the impression that the telephone is a World War II walkie talkie that must be yelled into. Even in the very first scene, before any of the murder and mayhem has occurred, she answers the phone with a blaring “HELLO?!” It just escalates from there. It becomes downright silly as she continuously grows louder and louder nearly every time she picks up the receiver. “Hello? Hello! HELLO?!?!” When the film delivers the iconic “the calls are coming from inside the house” bit, she decides that now’s the time to get that Oscar, so she begins screaming and hollering for Barb and Phyl, contorting her body in the process. It’s simply not believable at all and makes things all the more unfortunate since she’s clearly trying her best and failing. Hussey’s gone on to have a fine career and is indeed talented, but her decision to add the maximum level of emphasis to the word “hello” is ludicrous, although it has given my wife and I many laughs as we’ll often answer the phone in Hussey’s imitable fashion.

Though it did great business in its native Canada, Warner Brothers dropped the ball on the American release, changing the title to Silent Night, Evil Night due to fears of the original title drawing in the blaxploitation crowd. The tagline: “If this movie doesn’t make your skin crawl...it’s on too tight!” is fine, but a little wordy for my taste. Quentin Tarantino owns a print that he often screens during the holidays. Fortunately, Black Christmas has gone from being a cult film to a pioneering classic of the horror genre. Now if we can just stop people from trying to remake it. It doesn’t work. It’s never going to work, so just stop.

Comentários